click here to zoom

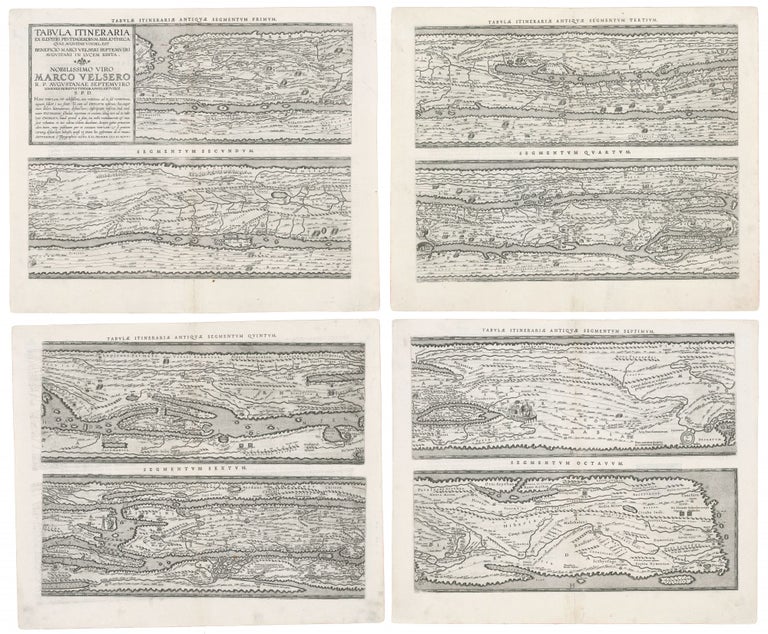

Roman Empire/ The Peutinger Table. ORTELIUS, A. [Antwerp, 1598/ 1624] Tabula Itineraria Antiquae… Four sheets, each approximately 16 ½ x 20 ½ inches. Centerfold reinforced with rice paper, a few marginal mends, else excellent. Though Ortelius’ source was itself a 13th century manuscript, a study of the map shows its source to have been a 4th century revision of a 1st century original: indeed, a remarkable survival. “…the Tabula Peutingeriana; a few local sketch maps … the representation of the Black Sea on the fragment of a soldier’s shield… and sketches of maps and plans appended to a manual for surveyors… this is the sum total of the Roman maps known to us” (Bagrow). Due to progressive decay of the original Peutinger, van den Broecke says that “Ortelius’ version is now the most reliable representation” of the map. Indeed, nearly all of the features of the original Peutinger are preserved in Ortelius’s engraving. The original Peutinger manuscript (now preserved in the National Bibliothek in Vienna) was a single, long parchment roll, approximately 22 feet long and little more than one foot wide. For purposes of preservation, it had been divided into twelve sheets, the first of which had been lost by Ortelius’s time. It is believed to date from the 13th century. References to early Christianity on the map as well as the use of the place-name Constantinople suggest 4th century alterations. However, the presence of Herculaneum, Oplontis, and Pompeii on the map suggests a first-century origin, as these towns were utterly destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. The unusual design of the map appears to have been dictated by its original medium: it is likely to have been drawn on papyrus, which would place no limits on length of the document but would severely constrain its width. Consequently, distances from east to west are shown at larger scale than those from north to south. In fact, roads running north to south are often shown running parallel to those running east to west. Actual distances are given between specific points along a given road. The usefulness of such a map presupposes the existence of a reliable, well-established road system: the traveler only needs the itinerary to know which road to take and how far it is to the next staging point. Direction of travel is of no concern; for that, one need only follow the road itself. The map is a testament to the achievement represented by the Roman road system. Though the loss of the first sheet of the Peutinger eliminated most of the British Isles and the Strait of Gibraltar, the remainder of the map spanned virtually the entire world known to Rome. It even encompasses areas that the Empire could not: Mesopotamia, Persia and India. Approximately seventy thousand miles of road appear on the map. Part of what makes the map so important a document is the amount of local detail. Not only towns but also staging posts, spas, palaces, and granaries are all shown on the map –some only by name, but many are marked with symbols as well. Rome and Constantinople are given pride of place and are represented by seated, Imperial figures. Two sections of the Peutinger map were engraved by Markus Welser in 1591. Ortelius was dissatisfied with this work so in 1598 commissioned Welser to produce a manuscript of the map in eight sheets to be engraved and added to the Parergon. Sadly, although he oversaw their production, Ortelius never lived to see this map printed. Shirley 212; Harley, J. B. & Woodward, D. The History of Cartography vol. 1 pp. 238-242; Bagrow, L. History pp 19; van den Broecke 227-230 (state 3).

One of the few surviving maps from the Roman Empire, delineating a foundation of its greatness--its extensive road system. Ortelius’s edition is considered the most accurate of this itinerarium pictum or “painted itinerary”--a visual guide to the Roman road system indicating travel distances, staging posts, towns, and other features of import to travelers. “In Renaissance Europe the first printed facsimile of an ancient map was probably the engraving of the Peutinger map commissioned by Abraham Ortelius” (Harley & Woodward).

Sold