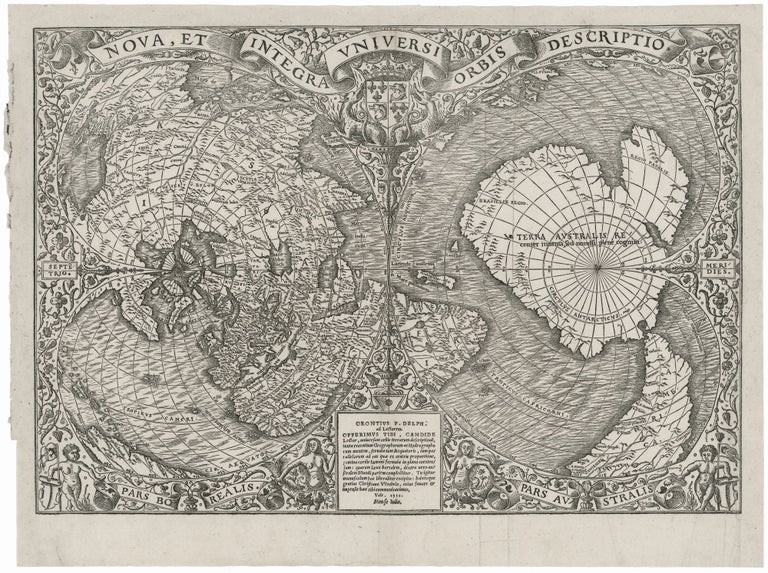

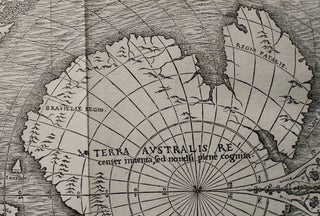

World. FINE, O. [Paris, 1531 [1532]] Nova, Et Integra Universi Orbis Descriptio . . . Orontius F. Delph . . . 1531 Mense Julio. 11 3/8 x 16 1/4 inches. Woodcut with a strong printing impression. Top & right side margins expertly extended with minor replacement of printed area at top right; overall near excellent. Simply locating South America and Brazil on this very intricate woodcut is itself a considerable challenge, since these areas appear, in separate parts, in three distinct sections of the map: at lower right, lower left and upper left. Taken together, these segments provide numerous coastal place names for Brazil and South America drawn from Vespucci and Portuguese explorers. Particularly interesting is that the place name, Brazil, appears here as “R. Brazil,” reflecting an early stage in the name’s evolution from that of a river (where brazilwood was found in quantity) to its eventual use as a designation for the country. Another form and location of “Brazil” also appears elsewhere on the map as explained below. Despite its relatively advanced geography, we still witness in Fine’s map the struggle to reconcile new discoveries within a general framework that itself was not verifiable at the time. In particular, the geographic relationship between the then emerging American landmass with Asia was far from settles at the time. Fine opted, it seems arbitrarily, to connect all of America to Asia here. This is especially remarkable in the face of Magellan’s voyage, which, if nothing else, would have demonstrated the vast distance between South America and Asia. In another extreme case of erroneous integration of new discoveries, Cabral’s explorations of the Brazilian coast, and the place name (here, “Brasielie Region.”) itself, appear on the Southern Continent east of Africa. This map also highlights one of the still unexplained mysteries of early cartography. Because of the projection used here, the map emphasizes the large, mythical, southern polar continent that is here, and by other early maps, presented as accepted fact. Remarkably, this landmass is very similar in shape (though not in scale) to present-day Antarctica. The resemblance is so uncanny that Fine’s map has been offered as evidence of the survival of ancient geographic knowledge or even, as a recent theory suggested, of the earth having once been mapped by extra-terrestrials. As unlikely as these ideas are, the fact remains that the precise delineation of the southern continent here and on other early maps remains not fully explained. Fine’s intricate woodcut employs the elegant double cordiform, polar projection. Despite its complexities, it proved attractive to a number of cartographers, including Mercator for his important map of 1538, and then to Italian mapmakers a decade or so later. First issued separately in 1531, the map’s earliest appearance in a text was in the 1532 Paris edition of Johann Huttich and Simon Grynaeus's Novus orbis regionum, a collection of travel accounts that had also been published in Basel several months before. Oronce Fine (1494-1555) was accomplished in many areas and published works in mathematics, cartography, astronomy, and instrument-making. He was the first Frenchman to absorb and explain many the period’s advances in these fields. Also, as can be seen from this work, Fine was also a very talented wood engraver and was one of the leading book illustrators of his day. Shirley 66 (state 1); The World Encompassed 64; Suarez, T. Shedding the Veil, 19; 90a, 106a, pl. XLI; Karrow, R. Mapmakers of the 16th Century, pp. 179-80 (27/4.1).

The rare and desirable first state of this important, early world map that provided “a rendering considerably in advance of any others printed earlier” (Shirley). With its crisp, dark impression and uniform strike, which are rarely seen in examples of this map, this is the most attractive example we’ve seen of this remarkably intricate map.

Fine’s was one of the few, obtainable world published during the Discovery Period that could be considered up-to-date for its time. In fact, many regions of the Americas begin to come into focus for the first time on this map. For example, it provides generally accurate representations of Florida, the Gulf Coast and the Gulf of Mexico, the latter based on Pineda and Cortez. Cortez’s important explorations along the west coast of Mexico are shown here for the first time on a printed map. Fine’s was also the first printed map to acknowledge by name Magellan’s circumnavigation by designating the sea just west of the southern tip of South America “Mare magellanicum.”

Sold